Folly of Peering Ratios

Introduction

Internet Service Providers peering policies fall roughly into four categories: Open, Selective, Restrictive, and no-peering. Those with an Open Peering Policy peer with anyone in any location(s), while Selective and Restrictive Peers use pre-requisites to screen prospective peers. One potential prerequisite is a “Not to Exceed” Peering Traffic Ratio which specifies the maximum allowable asymmetry in traffic exchange to be considered a “peer”. This of course excludes content heavy ISPs and Content Companies from settlement-free peering relationships. But does this make sense? Is there a technical and/or business rationale for using peering ratios in this manner?

Several hundred people attended the Peering Birds–of-a-Feather session at NANOG 35 where this issue was debated. During and after the debate, dozens of seasoned peering Coordinators discussed and debated the six strongest arguments for using peering ratios as a peering candidate discriminator. This paper highlights and discusses both sides of this heated debate.

(Editor’s note: The NANOG 35 Peering BOF Debate was held in the middle of the Level3-Cogent de-peering event that led to a partition across parts of the Internet. Since then, the Level3-Cogent peering has been re-established with no information released regarding the terms of that peering. However, an observant Peering Coordinator noticed that the Level3 Peering Requirements no longer include explicit peering ratios to be maintained.)

Peering Prerequisites

Obtaining Peering with companies with an Open peering policy can be as easy as a phone call and typing a few lines of router configuration. The technical component of peering is pretty straightforward.

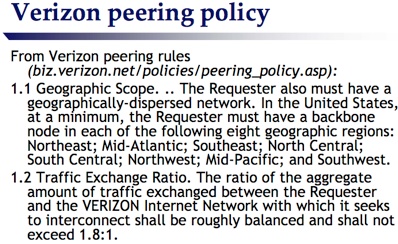

It is slightly more difficult to negotiate peering with a Selective Peer - one that has some peering prerequisites. During these initial peering discussions one is likely to hear a variety of peering requirements including traffic minimums, 24/7 NOC and contact information exchange, peering upgrade policies, number of interconnections and geographic distribution requirements, etc. There are rational technical and operational reasons for each of these. Occasionally, peering requirements include a “Not to Exceed” traffic ratio to ensure that aggregate peering traffic ratios will not exceed a particular ratio (quoted in Out:In – not to exceed 2:1 is a common requirement).

The Peering Coordinator Community put on a debate on the rationality of peering ratios as a peering discriminator at NANOG 35 in Los Angeles. During that debate, and during the subsequent informal debates afterwards, the consensus was that this metric was neither technically sound nor business rational.

For the duration of this paper we will present the strongest arguments on both sides of the issue. We present the strongest arguments for using peering traffic ratios as a peering discriminator, and then the counterpoint(s) discrediting the argument.

In a nutshell... (Summary)

In the heated discussions surrounding this topic there were six flavors of arguments put forth to support peering traffic ratios as a peering selection criteria.

Argument #1 - “I don’t want to haul your content all over the world for free.” This argument is countered with the observation that, whether peered with a content heavy or an access heavy ISP, the aggregate load on the ISP backbone is about the same and that the ISP is being paid by its customers for providing access to that traffic. It is not hauling the traffic for free.

Argument #2 – “OK, but there is massive asymmetry here. Look at how many bits miles I have to carry your content, while you have only to deliver your content across the exchange point.” Regardless of whether peered with content or access the load on your network is about the same; the access or content traffic has to traverse your network to get to your customers. The asymmetry is simply a reflection of the currently popular HTTP traffic profile.

Argument #3 – “As an Access Heavy ISP, I don’t want to peer with Content Heavy ISPs, because doing so will screw up my peering traffic ratios with my other peers.” The analysis and diagrammed traffic flows in this paper prove this assertion true, however, the argument is circular: ‘Peering Traffic Ratios are valid criteria because they support Peering Traffic Ratios with others.’

Argument #4 – “I want revenue for carrying your packets.” While this argument is business rational, peering traffic ratios are a poor indicator of the value derived from the interconnection.

Argument #5 – “My backbone is heavily loaded in one direction – I don’t have $ to upgrade the congested part of my core without a corresponding increase in revenue.” This loading problem can better be solved with better traffic engineering, with more resources for the core or by temporarily postponing all additional peering until the core is upgraded. Introducing a peering traffic ratio requirement is at best a temporary solution and signals a poorly managed network – a bad image for peers and transit customers alike.

Argument #6 – “I don’t want to peer with anyone else. Peering ratios help me systematically keep people out.” This is an understandable (although seldom articulated out loud) argument but is a poor defense for peering traffic ratios per se since it is an arbitrary discriminator; one could just as well have specified the size of the backbone core, the market capitalization or debt structure, or an extremely large number of distributed interconnect points.

Peering Traffic Ratios emerged years ago in the Internet as a peering candidate discriminator, but appear to have their roots in the PSTN world. Ratios reflect the telephony settlement model of buying and selling minutes, where the traffic difference between in and out is used for settling at the end of the month. However, the Peering Traffic Ratio discriminator model for the Internet interconnection fails because traffic ratios are a poor indicator of relative value derived from the interconnect.

The next few pages will go into more detail for each of these arguments, and then talk about several problems with using peering ratios as a discriminator.