Why Peering Ratios?

Argument #3 - “I don’t want to peer with Content Heavy ISPs because doing so will screw up my peering traffic ratios with my other peers.”

Let’s understand this argument with another example.

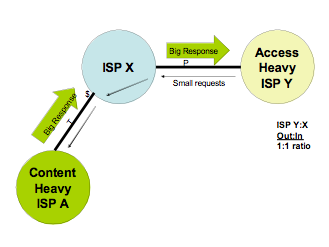

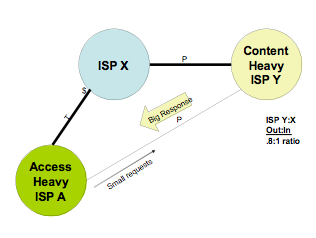

Figure 3 – Before Eyeball Heavy ISP Y peers with Content Heavy ISP A

Pictured here (figure 3) we have a snapshot of a part of the Internet that includes a Content Heavy ISP A, his upstream ISP X, and a peer of ISP X that we call Access Heavy ISP Y. Being Content heavy means that the small requests coming in are answered with large responses. The directed lines and their width highlight the traffic flows between Access Heavy ISP Y customers who request content from Content Heavy ISP A. Assume that the upstream ISP X and ISP Y peer with each other, and that the Traffic Ratio between ISP X and ISP Y is 1:1 in this initial scenario.

Now let’s assume that Content Heavy ISP A peers with Access Heavy ISP Y (see figure 4 below).

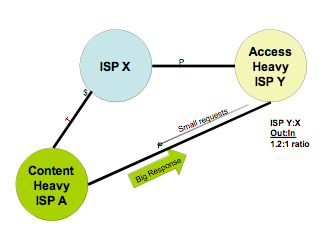

Figure 4 – After Eyeball Heavy ISP Y peers with Content Heavy ISP A, ISP Y ratios with ISP X are worse (ISP Y appears to ISP X to be more content-heavy than before). Let’s consider the effect.

The traffic between Access Heavy ISP Y and Content Heavy ISP A no longer traverses ISP X but instead traverses the direct interconnection. What is the impact? Migrating those large traffic flows away from the ISP X to the ISP Y interconnect make ISP Y appear to be more content heavy to ISP X than in the previous situation. Why? There is now relatively less content going to ISP Y from ISP X, while the same amount of content is coming from ISP Y. This makes ISP Y’s ratios with ISP X slightly worse, maybe 1.2:1 now, after the peering.

Conclusion 3A: If an Access Heavy ISP peers with a Content Heavy ISP, it can adversely affect its peering traffic ratios with its other peers.

Now let’s consider the opposite case – what happens when a content heavy ISP peers with an Access Heavy ISP? What happens to the Content Heavy ISP’s peering traffic ratios with its other peers?

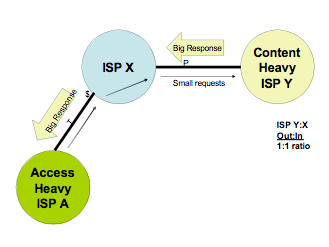

In this next picture (figure 5) we have an Access Heavy ISP A that purchases transit from ISP X, who has a peering relationship with Content Heavy ISP Y.

Figure 5 – Before Content Heavy ISP Y peers with Access Heavy ISP A

Small requests from Access Heavy ISP A’s customers generate large responses from Content Heavy ISP Y’s content customers. Let’s again assume here that ISP X and ISP Y have a 1:1 peering traffic ratio to begin with.

Now ISP A and ISP Y peer with each other, resulting in the following:

Figure 6 – After Content Heavy ISP Y peers with Access Heavy ISP

All traffic between ISP A and ISP Y now traverses the direct interconnection, shifting a large chunk of traffic from the Y:X peering relationship to the Y:A peering relationship. Now ISP Y appears less Content Heavy (from ISP X’s perspective), improving his peering traffic ratios with ISP X and others perhaps to .8:1.

Conclusion 3B: If a Content Heavy ISP peers with an Access Heavy ISP, it can positively affect its peering traffic ratios with its other peers.

Counter-Argument: But herein we reveal the folly.

(False) Conclusion 3: Peering traffic ratios are valid discriminators because they help maintain peering traffic ratios with other (existing) peers.

While demonstrable, THIS IS A CIRCULAR ARGUMENT for the general question at hand.

Consider the simplified restatement of this argument: “Peering traffic ratios are a valid metric because they support (other) peering traffic ratios.”

When confronted with this circularity the advocates offer argument #4.