I was at the airport waiting in the gate area for my flight from Detroit to Los Angeles. The gate agent called me up to inform me that the already delayed flight will most likely be cancelled, and that she has rebooked me on the next flight to LA, about 10 gates down the terminal. That flight will leave in 10 minutes. I ask that my work colleagues be rebooked as well with me and she obliges, so the three of us walk to the new gate and board the new plane, just in time for it to depart. Or so we thought.

The flight didn't take off on time. For thirty minutes or so we witnessed clearly agitated people getting on the plane, agitated, disheveled, complaining about something, out of breathe but boarding our plane. These people were clearly distressed. After a dozen or so people board, several came back to the front saying their assigned seat was taken and so they plopped down in first class. The flight attendant said "OK just sit anywhere we have to leave." The door closed and we took off. After take off I learned the story of the agitated people.

As it turned out, shortly after we had left the original gate, the gate agent announced the cancellation of that first flight. She made the following announcement:

"Ladies and gentle, we regret to inform you that flight 234 to Los Angeles has been cancelled. We will work to rebook you on a later flight, but in the meantime, we have a flight to LA leaving in 10 minutes at gate 34, about a 5 minute walk from here. We can take about 12-15 of you. If you would please progress to gate 34 in a calm and orderly fashion we will handle your rebooking on that or a later flight there. Please proceed to gate 34 in a calm and orderly fashion."

Given this context, can you guess what happen? Is it not predictable what would happen?

Sure enough, the 154 passengers rushed to gate 34 in a slight panic. The line developed at gate 34 and the gate agent processed people in order until people started circling around the gate agent to plead their special case. "My band plays tonight", "I am already late to my sisters wedding", "My business meeting starts one hour after I land", "I can not be late to my next flight", etc. The orderly line to get onto this next flight turned into a "make your case" mobfest. Those that were aggressive and/or convincing were given the boarding pass, perhaps just to get them out of the gate agents presence. The rewarding of behavior led to louder and more aggressive acts in line. You can imagine the situation. The notion of fairness, engraved in our minds, kicked in and led to the airport and Detroit police being summoned to the gate to calm things down and restore order.

Whose fault is this? Before you state the obvious, that the airline is responsible, do you place any blame on the passengers? Do they not have control of their actions? Or are we wound up like an involuntary muscle forced to act even if we do not know why.

In the U.S. most people claim that the airline is 100% responsible for mob scene, for the pushing and shoving, for the incivility and selfishness. They argue that the gate agents rewarded the bad behavior and people were justified in playing by the gate agents rule - those that would be aggressive and convincing in their case would be rewarded. This is the game and those who would win would adopt this winning strategy. It is rational and it would be irrational to not be aggressive and have no chance to board this next flight.

A small minority in the U.S. say the airline is not 100% responsible, that we are responsible for our actions regardless of the context we find ourselves in. To say the airline is 100% responsible is to allow people to dismiss civility and responsibility for their own actions because they were placed in a bad situation. If true, then getting stuck would provide a free pass to whatever behavior we chose, knowing that someone else would be blamed. The people in this camp see folly in "push and shove, yell, be uncivil, the airline is to blame for putting me in this predicament."

As the 80's rock band Devo so eloquently put it, "Are we not men?"

It was interesting to see that half of the Europeans in audiences where I presented this story believed the airline was 100% responsible, but the majority believed that the people were up to 40% responsible. Perhaps the Europeans are more inclined towards personal responsibility, are less ruled by the context they find themselves in.

In any case, clearly context is an important factor in behavior and we seen the same thing in the Internet Peering Ecosystem. Internet service providers are driven by their position in the Internet Region. Their positional power determines their motivations, which in turn drives their behavior. Much as the passenger behavior in the story above is predictable, so too is the behavior of the players in the Internet Peering Ecosystem.

We will see this as we discuss the history of Internet Peering. I find this to be a fascinating topic because throughout my studies, these disparate players interconnect and expand organically, reacting and morphing as if they were collectively part of a living organism.

[This section is based on Lyman Chapin's discussion in http://www.interisle.net/sub/ISP Interconnection.pdf.]

In the early 1980's the ARPAnet was restricted to government and government contractors, and commercial networks could not connect. The NSF sponsored the CSNet project to interconnect the computer science departments together which ultimately highlighted a problem.

Both sides assumed there was enormous complexity involved in reconciling the different network AUPs, and that the corresponding settlement administrative and contractual issues associated with interconnection were formidable.

This is where peering was first invented as "interconnection without explicit contracts." The motivations were to avoid complexity, to interconnect their networks as simply as possible.

I worked on the NSFNET at the beginning of its contract with Merit Network. The NSFNET was the core of the Internet, with the task of interconnecting the NSF-funded regional networks together.

Through the NSFNET, the researchers at one supercomputing center could share data with researchers at another supercomputer center for example. The networks attached to the NSFNET were the NSF sponsored regional networks and we (Merit) maintained a database for keeping track of who was authorized to connect to the backbone. Four additional network attachments to the NSFNET were made only with the blessing of the NSF, and was a highly politicized activity. Much like a planned economy, the government controlled things, which provided stability, funding and a difficult time for private sector companies seeking to compete against the government to provide Internet services.

It was at this time that the Regional Tech's Meetings were key – we met a few times a year to share how the NSFNET was doing, and the regional network techs shared what they were seeing This was a truly open and cooperative activity. We shared information openly, discussed problems and solutions in a collegial basis.

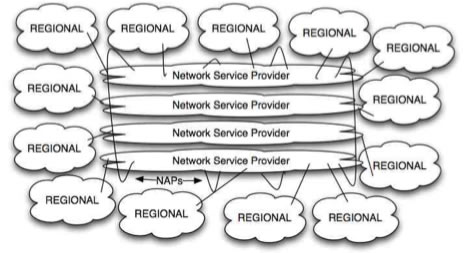

Around 1993 the NSF recognized that the Internet had grown tremendously, and that the government need not operate the Internet backbone any longer. The NSF assembled a team of key stakeholders to design a transition architecture to maintain the connectivity for the regionals while allowing commercial ISPs to compete for the Internet access contracts. The resulting architecture is shown here.

In this new Internet Peering Ecosystem, the regional network could choose from a set of competing Network Service Provider. There was a caveat however; to use NSF funds, the regional networks could only purchase Internet access from NSPs that interconnected at the three of the four "priority Network Access Points", also known as NAPs. The NSF awarded the designation of NAP to Sprint, PacBell, AADS, and eventually MAE-East. The last component of the architecture was the Routing Arbiter, a contract that Merit won. This piece continued the routing database activities in the NSFNET but expanded into the commercial sector. Collectively, the combination of NSPs and NAPS (and to some extent the Routing Arbiter) provided a competitive commercial replacement for the NSFNET backbone. It took a few years for the regional networks to completely migrate off of the NSFNET.

My role in the Routing Arbiter project was to likewise come up with a business plan to make the operations meeting self-sustaining (not requiring any NSF funds). The regional techs meetings were renamed the North American Network Operators Group (NANOG) and Mark Knopper and Elise Gerich developed a charter. (As a brief aside I hated the name - I didn't care for the sound 'NOG', but it seems to have stuck and everyone got used to it. In fact, many other 'NOGs' have emerged around the world.) I came up with the business plan for making NANOG self sustaining and I took the role of NANOG 'chair', coordinating a team to manage the meeting logistics, the speakers and topics, to introduce the speakers, etc. I chair the NANOG meetings from 1995 to 1998.

It was during this transition stage that I first noticed that it was much more difficult to get speakers for NANOG meetings. No one would share that there were problems on the Internet, certainly not with the part that they managed. My old regional techs friends that went to commercial companies apologized but pointed out that the company had proprietary interests here, and that anything bad would be used against them in the market place and that the company had marketing messages that they wanted to get out; any other message but company employees would dilute the marketing message.

The context of commercial Internet interests put at odds the community desire to understand this new and emerging commercial internet and corporate interests. This conflict continues today; it is very difficult to get operators to speak on operations issues, lessons learned or cooperative solutions.

From a peering perspective, interconnections went from being a regular announcement at the regional techs meeting, to being a private matter between two parties. Commercial ISPs were not interested in letting anyone know who recently attached and at what capacity. This would make it easier for competitors to gauge them and perhaps cherry pick the largest customers. Interconnections became proprietary and was one more area that was not to be discussed from a stage, but it was certainly a heated topic discussed with vigor over drinks at the bar.

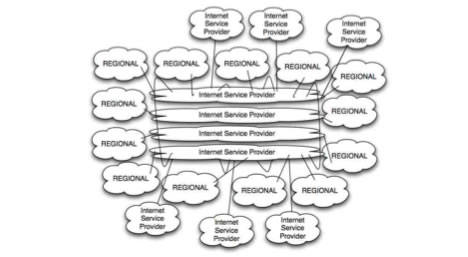

The Internet continued to grow and there was a massive growth in the number and type of ISPs now reselling access to the Internet.

The shared ATM-based peering fabrics at the NAPs had congestion issues, leading to the larger Tier 1 ISPs connecting to each other using point to point circuits. The significance of the regional networks decreased as they represented a smaller and smaller percentage of Internet traffic. As a result, the designation of NSF NAPs and NSPs became of little consequence.

Commercial Internet - '96-'98

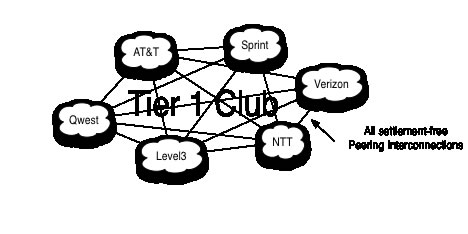

Congestion at the NAPs, referred to as "congestion points" by detractors, led to a migration to private peering by the Tier 1 ISPs around 1998.

The fact that the NAPs were operated by competitors (Sprint, PacBell, AADS, MFS/WorldCom) provided additional business motivations to make the architectural transition for the Tier 1 ISPs. The other force was the desire to not use one's own NAP – the UUNet ISP for example loathed to peer at MAE-East, a wholly owned subsidiary.

I spent a lot of time with the Tier 1 ISPs trying to understand why they pulled out of the NAPs, what pain points they faced, and when they would use exchange points again.

What I learned was that there was a real problem with the provisioning time for the point-to-point circuits. They were being delivered 18 months late! And since the Internet traffic continued to double every year, this presented a significant problem. Many resorted to circuitous routing to avoid congesting their circuits. The other issue with circuits was the cost. I shared what I learned from the Tier 1 ISPs in a white paper called "Interconnection Strategies for ISPs" that proved that private peering at an Internet exchange is more economical than point-to-point circuits if one can interconnect with five others,

In addition, carrier-neutral exchange points could provision fiber cross connects in days, not months. Further, by building into a carrier neutral exchange point, the Tier 1 ISPs were not supporting their competitors. Finally, where the NAPs had used ATM, the carrier neutral exchange points adopted ethernet, a interconnection technology most ISPs prefer. All of these factors led to a resurgence of Tier 1 and Tier 2 ISP peering at the carrier neutral Internet exchange points.

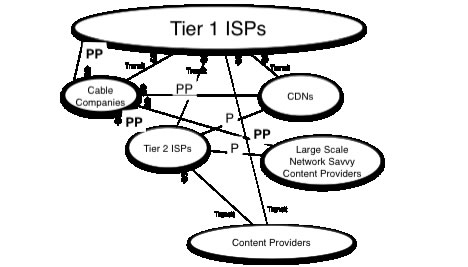

Even as the Internet continued to grow organically, there emerged an identifiable structure.

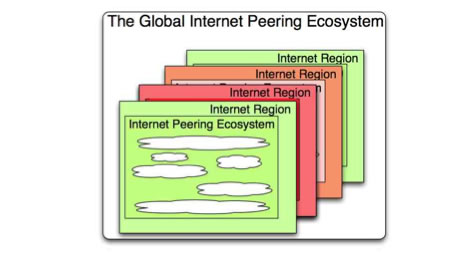

The Internet architecture can be modeled as a Global Peering Ecosystem. The Global Peering Ecosystem is a containment abstraction that helps us understand Internet Interconnection dynamics.

Think of the Global Peering Ecosystem as a set of "Internet Regions", usually loosely associated with countries.

Each Internet Region contains an Internet Peering Ecosystem that consists of a set of network service providers interconnected in some business relationships.

I have studied dozens of Internet Regions around the world and they all tend to have at least these categories of participants in the Internet Peering Ecosystem.

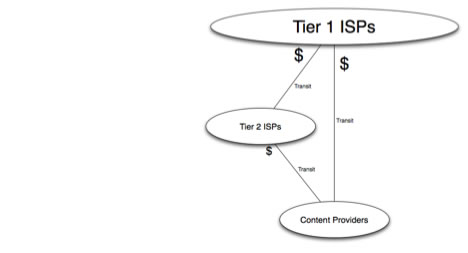

The Tier 1 ISPs have access to the entire regional routing table solely through their free peering relationships. The Tier 2 ISPs are different in t that they need to purchase transit from someone in order to reach some destinations within the Internet Region. They have the motivation therefore to peer with each other to reduce that transit expense. The content providers differ in that they generally do no t sell Internet Transit, don't tend to have a backbone or even much of a network engineering team.

The Tier 1 ISPs are in a good position, aren't they? All traffic in this picture goes through them, and they get paid by the eyeballs that request the content, or the content that connects to them or even perhaps both.

Note however that gouging didn't occur here, because there were usually multiple Tier 1 ISPs completing for business, and there was also the opportunity to peer with the Tier 2 ISPs that could reduce the transit load. There were two alernatives for getting content to the eyeballs- competive transit and peering.

But from 2000-2002 we saw a morphing of the ecosystem, a system that had adverse effects on the Tier 1 ISPs..

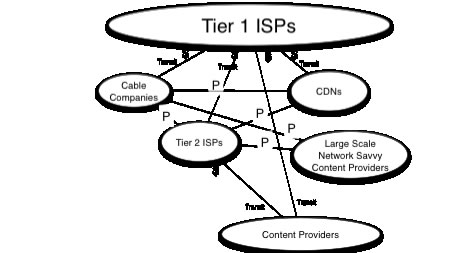

The middle of the Internet Peering Ecosystem got fat.

The cable companies in the U.S. came into the peering ecosystem as "open Peers", willing to interconnect with anyone for free provided there was enough traffic to make it worth while.

The largest content companies (Large Scale Network Savvy Content Providers) got into peering to improve and control the end user experience. This was a universal motivation for content companies – they wanted to save money yes, but #1 was the end user experience.

And of course, just as the Tier 2 ISPs peered with each other, the cable companies peered with each other. All of these like-minded players peered with each other, resulting in a massive shift of traffic away from traversing the Tier 1 ISPs. Peering not only saved on transit fees, it also improved the efficiency of the Internet by reducing the number of hops between content and eyeballs.

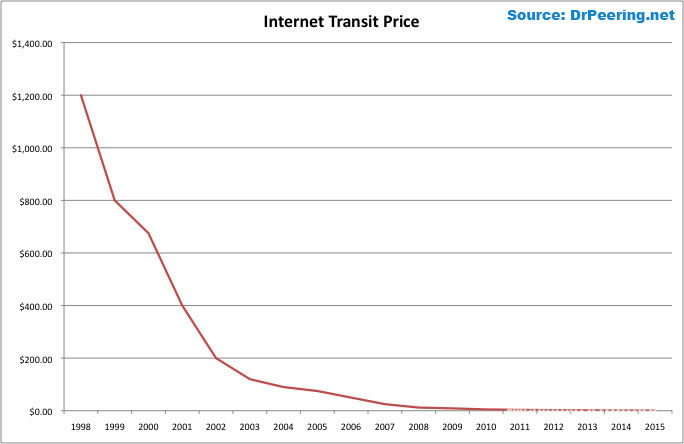

Two trends were very active in the Internet Peering Ecosystem. First, the price of transit dropped every year. I started tracking the price of transit when I started at Equinix in 1998 when the price was $1200/Mbps. Today, in 2011 the price of transit is a few dollars per Mbps. Every year the ISPs claimed it couldn't go lower, and that no one was making money at these prices. Every year the price dropped again.

The second trend was that the Internet technologies was getting good enough to support video. By 2006, short video clips on youTube was working well and the business models was enabled by the dropping cost of Internet Transit.

Cisco estimated that by 2013 80% of all Internet traffic will be video. Discussions with ISPs in 2011 suggest that at least 40-50% of all Internet traffic is video today. These two trends amplify the importance of an efficient Internet Peering Ecosystem - to serve up this video traffic, ISPs need to be able to deliver large amounts of bits for very little cost and with very few glitches.

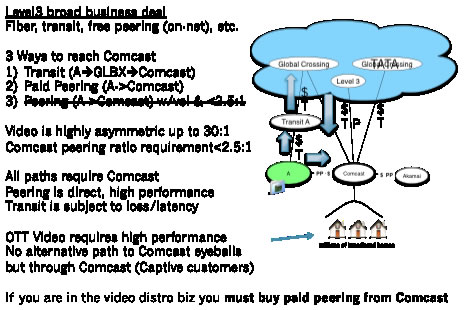

The U.S. cable companies (mostly Comcast at this stage) started exploiting the fact that there is only one way to get to their customers eyeballs – through their cable company network! They installed a peering ratios prerequisite so that any entity that sent more that 2.5 times the traffic to the cable company than they received would not qualify for free peering.

Since video is or soon will be the dominant Internet application, and it is massively asymmetric (as high as 30:1), and since Comcast customers are predominantly eyeballs pulling down content from the Internet, very few peering candidates have a balanced ratio to offer. So Comcast created a peering policy that led to revenue from paid peering. For over a decade I had been searching to understand and document paid peering and finally I had found it. Here is how it works.

Today we are seeing the emergence of a new power player in Comcast. The positional power is based on the fact that the eyeballs that consume Internet traffic are "Captive", only reachable via a path through Comcast. We need to explore a couple of other key aspects to this network situation.

A content company or content distributor has two choices for getting its content to the eyeballs. It could purchase transit and its upstream provider would get the traffic to the eyeballs. The alternative is to peer with Comcast. Comcast has a peering prerequisite of a haelthy chunk of traffic, but that isn't what disqualifies most prospective peers form free peering with Comcast. Comcast requires a traffic balance of less than 2.5:1.

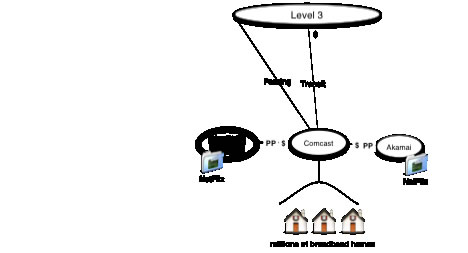

In this illustration of the power of captive access power peering, a video distributor called NetFlix purchased CDN services from Akamai and Limelight networks among others. Both of these two CDNs are paid to get the video objects as topologically close to the eyeballs as possible, and therefore have purchased paid peering from Comcast, the largest cable company in North America. Today the price of paid peering from Comcast is about the same as the price of Internet transit, so the logic is, if you have to get the content to the eyeballs anyway, and it costs the same, why not send it to Comcast directly and pay them instead or you transit provider? The traffic will get there quicker, with less hops so more reliably and it costs the same.

It should be noted that there are religious views about peering vs paid peering, The content providers would argue that the access networks customers are requesting that content and therefore they should not have to pay anything to give it to the requesters. Some argue that the content is the value and the access networks directly or indirectly ought to pay them! However, this argument has never gained traction on the Internet; access has alway been more powerful in peering discussions because there is no alternative to reach the millions of access network eyeballs, where there is generally an easy alternative for the singular content provider.

The other important factor in this scenario is that Level 3 is one of the transit providers for Comcast, and as part of a broader business relationship, Level 3 provides free peering to Comcast - that is, they both provide reciprocal and free access t each other customers.

These relationships are shown below.

Level 3 bids for the Netflix business and they win, undercutting Akamai. As a result, the NetFlix traffic moves from Akamai to the lower priced CDN that Level 3 offers. Level 3, since they are peering with Comcast, informs their peer that there will be some new traffic and that they will need to add additional Peering capacity. This is a common thing that peers do.

Who wins and who loses here? Akamai obviously loses the business, so the NetFlix revenue decreases. Comcast loses a corresponding amount of paid peering traffic and revenue. And Level 3 wins the business so the additional revenue gains. But Comcast loses again, because not only does it give up the paid Peering revenue from Akamai, it is also being asked to spend money on additional peering ports to handle that same NetFlix traffic over their free peering relationship with Level 3.

Comcast refuses to add capacity for free and suggests that Level 3 is "out of ratio" and needs to pay Comcast for paid peering. They argue that it wouldn't be fair not to charge them since they charge the other CDNs for paid peering. It would be an unfair competitive advantage if Level 3 didn't pay as well.

This dispute was very public and much like the airplane story in the beginning, there are opinions across the spectrum as to who is to blame for this context.

Level 3 ultimately acquiesced and paid (or the equivalent of paid) Comcast for paid peering.

We have seen that across the history of the U.S. Internet Peering Ecosystem, that the models have changed. The players and the relationships and the power positions evolve. The Tier 1 ISPs were in charge and received a piece of the traffic that directly (from a customer) or indirectly (from a customer of a downstream) traversed the Internet region. In this case, the Tier 2 ISPs could peer their traffic between themselves as an alternative to spending money with their transit provider. They could also select a different upstream ISP. So there was a choice, and the alternative of peering and an open market led to cost and performance efficiencies. The right things happened and the Internet Peering Ecosystem evolved in a good direction.

The Captive Access Network Power Peering scenario is problematic.

First, there is no alternative way to access the access network customers but to go through the access network either indirectly (through transit providers) or directly with peering of the paid or free variety. But since 80% of the Internet traffic is destined to be video, a massively asymmetric stream, and since the access networks will predominantly have eyeballs, the peering ratios clause will prevent free peering from happening.

So the alternatives are transit and paid peering. Since 80% of the Internet traffic is video, the ISPs become essential video distributors as opposed to general purpose packet pushers. Therefore, to do an effective job at delivering video for their customers, they must purchase paid peering. There simply is no choice.

Unlike when the Tier 1 ISPs ruled the Internet Region, there is no peering bypass that leads to a more efficient and perhaps less expensive alternative. All paths to the access network customers traverse the access network.

In the illustration example above, Comcast charged market transit prices for paid peering. But what prevents them from charging a higher price? What is the alternative for CDNs whose business is to get the web objects as topologically close to the eyeballs as possible?

Is the next Internet Peering Ecosystem model really that everyone pays the access networks to deliver the 80% video Internet traffic?

Thanks to Frédéric Libotte (BNIX), Pierre Bruyère (BELNET), Jon Terreele (BELNET), Scott Landman (JetStream)