Excerpts from The Internet Peering Playbook: Connecting to the Core of the Internet

In this page you will learn about Internet Transit, a service that provides access to the global Internet. We introduce the definitions and the service model, and then describe how Internet Transit service is offered, priced, and metered.

The author delivering his book at the African Peering and Interconnect Forum in Accra, Ghana

The Internet is a network of networks.

To get connected to the Internet, an entity must attach itself to an entity that is already connected to the Internet. It usually accomplishes this connection by purchasing a service called "Internet Transit”.

Definition: Internet Transit is the business relationship whereby an Internet Service Provider provides (usually sells) access to the global Internet.

From a high-level perspective, Internet Transit can be thought of as a pipe in the wall that says "Internet this way”. Customers connect their networks to their Transit Provider, and the Transit Provider does the rest.

Definition: An Internet Service Provider (ISP), also called a “Transit Provider,” is an entity that provides (usually sells) access to the Internet.

The primary business of an Internet Service Provider is to market, sell, and operate the Internet Transit service described next.

The Internet Transit service has two primary functions:

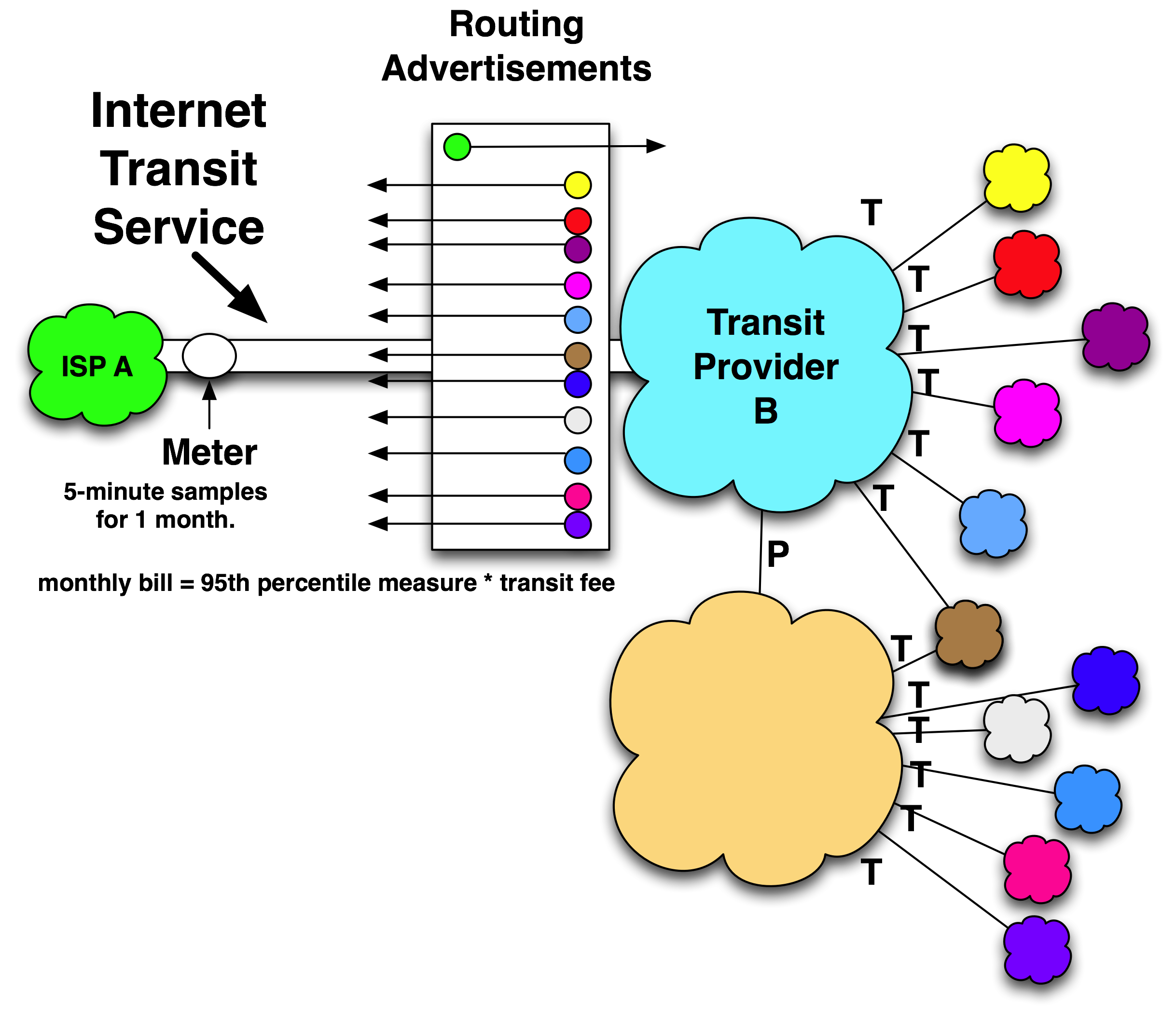

To illustrate, consider a customer (ISP A) purchasing the Internet Transit service from Transit Provider B as shown in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. The Internet Transit Service.

We will use graphical notations throughout this book. The different colored clouds represent networks attached to the Internet. The ‘T’ next to a line represents an Internet Transit relationship. The routing advertisements box describes which routes are “announced” between the Internet Transit customer (ISP A) and the upstream Transit Provider B. The arrows signify the direction of the routing announcement.

These routing announcements are propagated across the Internet. Transit Provider B announces to the ISP A the routes to reach the entire Internet (shown as many colored networks to the right of the Transit Providers). The ISPs across the Internet propagate this ISP A route so that all networks know how to reach the ISP A.

In summary, through the Internet Transit service, all Internet attachments know how to reach ISP A, and ISP A knows how to reach the rest of the Internet.

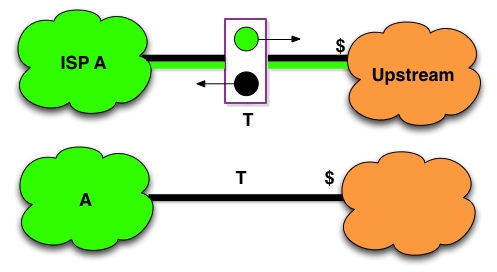

For convenience, we will also use the following equivalent notations (Figure 2-2) to indicate a transit relationship between a customer and the upstream transit provider.

Figure 2-2. Equivalent Internet Transit service notations.

The black circle is shorthand for a default route to reach the rest of the Internet. This typical and default arrangement can be inferred by identifying the two parties in the relationship with the “T” and the “$” symbol describing which party is being paid for the Internet Transit service.

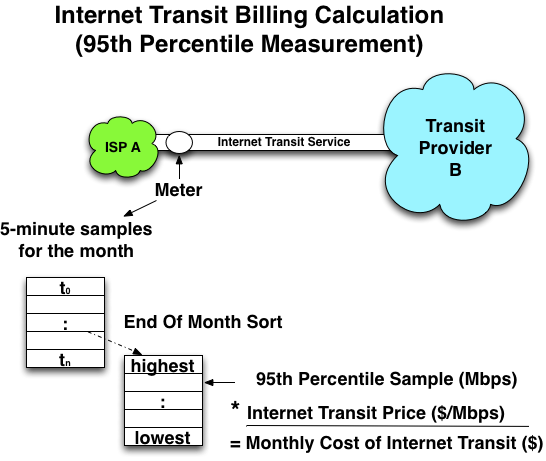

The Internet Transit service is typically a metered service outside of the residential market. The unit price for Internet Transit services varies widely, but the service itself is typically priced on a per-megabit-per-second (Mbps) basis, metered using the 95th percentile traffic sampling technique.

Definition: The 95th Percentile Measurement Method (also called 95/5) identifies a single measurement (the 95th percentile 5-minute sample for the month) to determine the transit service volume for monthly transit fee calculation.

The 95th Percentile Measurement Method is typically a three-step process, as follows (diagrammed in Figure 2-3):

Figure 2-3. Calculating the monthly cost of Internet Transit using the 95th percentile measurement methodology.

The basic Internet Transit billing model is simple:

Monthly Bill = Internet Transit Volume * Internet Transit Unit Price

Example:

If you signed an Internet Transit contract with a negotiated price of $5/Mbps (measured at the 95th percentile), and at the end of the month you sent 500Mbps (measured at the 95th percentile), what would be your transit cost that month?

Answer: 500Mbps * $5/Mbps = $2500 per month

How did the 95th percentile come into existence?

The Internet Transit pricing model went through three distinct pricing phases:

One question always comes up at this point in the peering workshops:

“Is 95/5 measuring traffic coming into the network or out of the network?”

The 95th percentile measurement uses the greater of in versus out, as shown in the following equation:

Monthly Bill = max(inAt95th,outAt95th) * Internet Transit Unit Price

But for the sake of simplicity, when we introduce equations from here forward, we will not clutter the equations with this in-vs.-out nuance. When we say 95th percentile, we know that what we really mean is the 95th percentile of the larger of in vs. out.

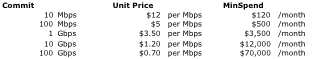

The Internet Transit pricing model gets only slightly more complicated when adding "commits".

To encourage the use of the Internet Transit service, and to compete more aggressively in the market, most ISPs provide pricing discounts for pre-committing to certain volumes of traffic (Table 2-1).

Table 2-1. Sample Internet Transit with Commits Pricing Table

Here we see an ISP that offers a price of $12 per Mbps for a monthly commit of 10Mbps, and a price of $5 per Mbps with a monthly commit of 100Mbps. These price points guarantee that the monthly transit fee will be at least $120 and $500 per month, respectively.

What happens if customers commit to 100Mbps but don’t use all of the 100Mbps in a particular month? They are still required to pay as if they had used the full 100Mbps.

What happens if they use more than the 100Mbps in a particular month? They generally will have to pay the metered rate on the volume of traffic they actually used. This rate is sometimes referred to as the "burst rate", but it is generally the same price as the commit rate.

We can describe this model formulaically as:

Monthly Bill = max(TransitVolumeAt95th*Price, Commit Volume*Price)

The Internet Transit with commits model typically involves contracts that state the price point for the agreed-upon commit level and the duration of the agreement. So, for example, a 1Gbps commit at $3.50 per Mbps might have a 1-year term. This is how the Internet Transit service is sold today.

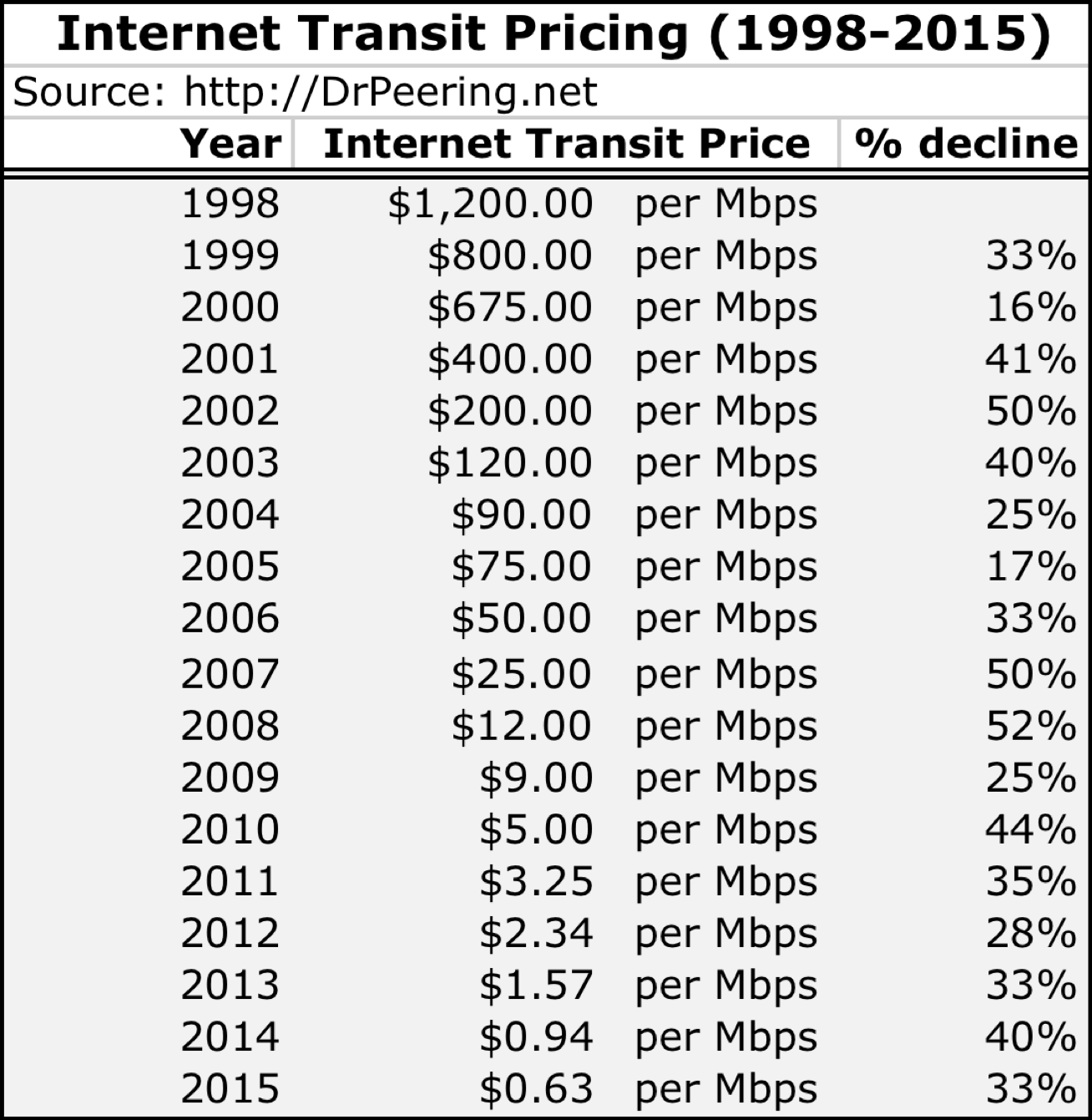

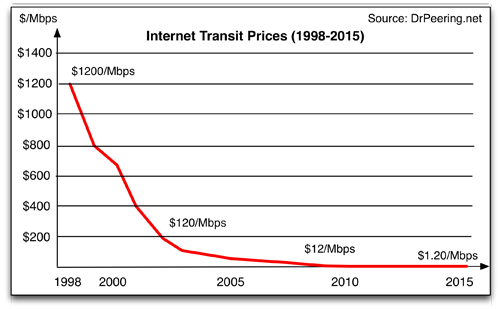

I have been tracking the price of Internet Transit since 1998, and as you can see from Table 2-2 and Figure 2-4, the prices for Internet Transit have dropped every year.

Table 2-2. U.S. Internet Transit Prices (1998–2014) Historical and Projected

It is worth pointing out that these data have always generated heated debate in the peering coordinator community.

Notes from the field.

Internet Transit Pricing Data and Controversy

The controversy over these numbers is related to the variability in service offerings and pricing. Further, the pricing schedules are often protected under a nondisclosure agreement (NDA), and generally not publicly available to systematically analyze. Some ISPs consider many variables when determining pricing. They might, for example, account for the number and size of the ports requested, type of the customer traffic (inbound vs. outbound), how that traffic would impact the ISP, the region(s) and market conditions at the location of the interconnection, etc. For these reasons, many would argue that there is no single market price for Internet Transit. The data are inherently flawed.

And they have a valid point.

My data are anecdotal and based on a variable and small sample size, polling maybe 30–50 people three to five times a year. The transit price points are collected on an ad-hoc basis at operations conferences that I attend every year. I ask ISPs and transit customers, "What is the going price for transit these days?” From the dataset I throw out the outliers and select the middle from the mass of numbers that fall within a narrow range.

However flawed this manual measurement system is, it remains one of the very few longitudinal measures of the market price for transit. Some of these measurements were based on or validated by contributed ISP pricing sheets. One can say "according to the conversations Bill has had with ISPs over the years, the transit prices have dropped roughly like this line." I would not recommend taking these numbers as anything but very rough indications—and a better mechanism is on its way as we start measuring in $/Gbps.

Besides, to focus on the individual data points is to miss the point.

The point is that the trend is unmistakable, and no one would disagree—because transit prices have dropped every year.

The other interesting thing I noticed is that every year the ISPs say to me things like, “Transit prices can’t get any lower,” and “No one is making any money at these prices.” And every year, the prices drop again.

Figure 2-4. Internet Transit prices historically decline every year.

The good news for ISPs is that Internet traffic volumes have always grown as well, and all indications are that this trend will continue for some time. Even though the price of transit has declined by around 30% per year, Internet traffic typically increases by more than 50% per year.

There is also some debate within the community on the qualitative differences between transit from a lower-priced provider and the Internet transit service delivered from a higher-priced provider. Higher-priced providers would argue that they have better-quality equipment (routers vs. switches, etc.), and better and more sustainable operations procedures that simply cost more to operate. They would argue that “you get what you pay for in the transit market”. They could be right, but I would also point out that I have not met very many paying customers complaining about the quality of service of lower-priced providers.

Some content providers prefer a transit service (paying customer) relationship with ISPs for business reasons. They argue that they will get better service with a paid relationship than with any free or “special deal”, bartered, or “peering” relationship.

Service-Level Agreements (SLAs) are contracts with financial penalties for failure to meet specified service levels. They are intended to punish an ISP for failure to meet the explicit customer expectations. Many Internet Transit customers I have spoken with have said that they felt comforted by these financial penalties, these “teeth.”

Internet Transit SLAs, however, are widely dismissed by the network operators as merely insurance policies. The ISPs I spoke with said that it is common practice to simply price the Internet Transit service higher when it includes SLAs, and with the increased pricing proportional to the likelihood of their failure to meet the SLA requirements. Further, the customer has to notice the SLA failure, file for the SLA credits, and check to see that credits are indeed applied. Some ISPs see SLAs as a way to simply increase margins without needing to improve the service.

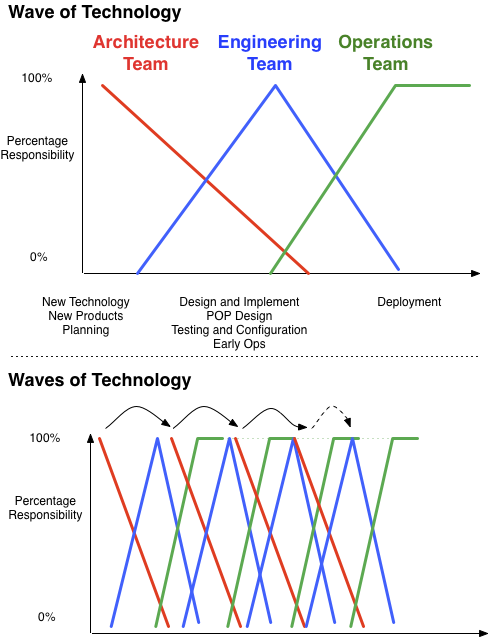

While a complete exploration of the ISP business models is beyond the scope of this book, a few commonalities across ISPs are worth highlighting. Every year the underlying technologies get better, cheaper, and faster. These advancements tend to come in waves. As a result, most larger ISPs have an Architecture-Engineering-Operations workflow, with responsibilities being transitioned between these disciplines as shown in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5 The Architecture-Engineering-Operations new technology waves and responsibilities.

When new technologies are considered for a network, the ISP Architecture team evaluates the applicability and designs a solution. Once accepted, the solution moves through a joint Architecture/Engineering development phase, during which the Engineering team increasingly takes over responsibility for the deployment of the technology. The Operations group takes over responsibility from the engineering team as the technology hardens and the logistical transition challenges are worked through. The Engineering team eventually is removed from the day-to-day operations activities of the technology, and the Operations team runs the technology in the production network.

This cycle continues as the next wave of technology becomes available and the Architecture team looks at its applicability. These technology waves apply to backbone infrastructure (routers, transmission gear) as well as edge devices (routers, switches, auxiliary services) and support systems.

These waves of technology are important because they enable the ISPs to compete more effectively in the Internet Transit market. Those with old equipment simply can't compete with the economies of scale realized by the large players.

To finish this chapter, let’s highlight a few important characteristics about Internet Transit:

That is what you need to know about Internet Transit. In the next chapter we will discuss the "tricks of the trade" that some have used in an attempt to improve the efficiency of their transit service purchase.

Here are a few discussion questions from the Internet Peering Workshop.

1. I am purchasing Internet Transit from ISP A for $5 per Mbps with no commits. At the end of the month I send 500Mbps and receive 800Mbps at the 95th percentile. What is my monthly bill?

A) $5/month B) $2500/month C) $4000/month D) $6500/month

2. I am purchasing Internet Transit from ISP B for $5 per Mbps but I am considering buying its 1Gbps commit transit product at a price of $3/Mbps. I still expect to send 500Mbps and receive 800Mbps at the 95th percentile. Should I commit to 1Gbps?

Answers to these questions along with related FAQs and supplemental materials are here:

http://DrPeering.net/books/The-Internet-Peering-Playbook/transit.php